If Ligonier Valley Could Talk: A Brief History of Ligonier, Pennsylvania

As the Ligonier Valley Historical Society, it’s our duty to share the history of our area. In our new blog series, If Ligonier Valley Could Talk, we’ll explore the histories of faded newspaper clippings and oral histories passed down from generation to generation in Ligonier Valley. Our next stop is the town of Ligonier, a jewel in the Ligonier Valley.

The winds of war were blowing in the mid-18th century as two great forces from Europe vied for possession of what is now western Pennsylvania. Both France and Great Britain understood that whoever controlled the Ohio Valley controlled all the resources of the Mississippi Basin. As settlers moved west in increasing numbers, few could have guessed the role the Ligonier Valley would come to play in determining the course of our nation’s history.[1]

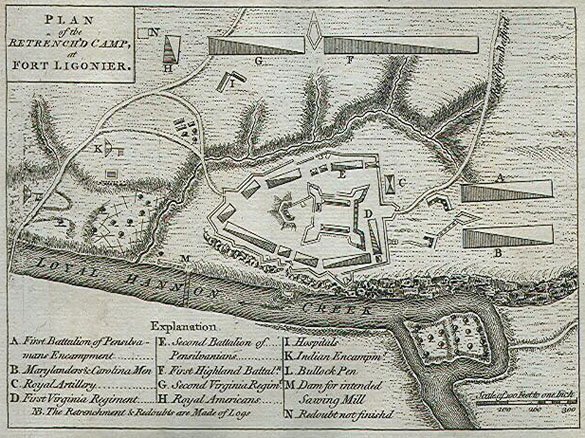

Fort Ligonier

During the French and Indian War in 1758, General John Forbes ordered the construction of a new road over the Allegheny Mountains to transport soldiers and supplies to present-day Pittsburgh on a mission to capture Fort Duquesne. The road became known as Forbes Road. In September of that same year, Fort Ligonier, named after Sir John Ligonier (commander in chief in Great Britain), was built at Loyalhanna. The fort served as a place for supplies and to prepare the British-American Army for an attack on Fort Duquesne. On October 12, the British successfully defeated the French at the Battle of Fort Ligonier.

Turnpike Influence

From the French and Indian War until the 1790s, what is now Ligonier saw very little, if any, settlement. The poor quality of the State Road, which roughly followed the Forbes Road, political instability, and the threat of Indian attack discouraged settlement. Even after the 1790s, few people called Ligonier home until the completion of the Philadelphia-Pittsburgh Turnpike in 1817.

At the completion of the turnpike, Colonel John Ramsey put up for sale plots of land near the site of Fort Ligonier. He wanted to call it Wellington, but most people referred to it as Ramseytown. The name was officially changed to Ligonier when it was incorporated as a borough in 1834.

The Turnpike brought slow and steady growth to Ligonier. Blacksmiths, wagonwrights, shopkeepers, livery stables, and taverns lined the Turnpike along what is Main Street today. Despite this development, Ligonier was not considered a destination. Most of the people in town were transients–teamsters, drovers, peddlers and migrant settlers.

John Ramsey also established the public square, now referred to as the Diamond. He required those that purchased lots build two-story brick buildings within seven years or pay a fine. While the Diamond today is seen as a decorative feature and community gathering space, it originally served as a “parking lot” for the horses and wagons traveling along the turnpike. The Diamond remained as such until 1894 when Ligonier joined the City Beautiful Movement. At that point, the Diamond was transformed into a public park with lamps, sidewalks, landscaping and a bandstand.

Transition Period

Ligonier continued to be a popular spot along the Turnpike until the mid-1800s when the Pennsylvania Railroad was built and bypassed Ligonier. Ligonier’s population began to drop. However, when the Ligonier Valley Railroad (LVRR) was completed in 1871, the town became a shipping center for lumber, wood products and stone. In becoming commercially significant yet again, Ligonier’s population doubled between 1870 and 1880.

In the midst of the transition from the turnpike to the railroad, Ligonier established itself as a summer resort for Pittsburghers. Once the LVRR was completed, Ligonier became even more popular, especially with the addition of Idlewild, a summer campground that eventually developed into the amusement park we know today.

In the early nineteenth century, Ligonier and Laughlintown—the neighboring town three miles to the east—were similar in population and purpose. At the end of the Turnpike Era, however, the development of the two towns diverged. Ligonier continued to grow because of its location on the Loyalhanna, the active promotion of an organized town and the establishment of the Ligonier Valley Railroad. Laughlintown, on the other hand, was bypassed by the railroad, and its population began to decline. Although Laughlintown was incorporated before Ligonier, the latter has become the dominant town in the valley.

The Future

Today, Ligonier, while preserving its small-town charm, is a popular summer destination for many. Outdoor attractions, local history and heritage organizations, shopping, and Idlewild Amusement Park help make Ligonier a thriving community. Fort Ligonier Days—a three-day event that features historic battle reenactments, top-rated juried crafts, delicious foods, delightful musical entertainment, and a grand parade—help to bring more than 100,000 people to our community every year. With so much happening in this small community, what will you choose to do next?

Additional Readings

[1] Shirey, Sally. Images of America: Ligonier Valley. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2001.

[2] https://www.compassinn.org/history-of-ligonier

[4] https://www.ligonier.com/history-of-ligonier/

‘Tis the Holiday Season in Ligonier Valley

Christmas has long been my favorite time of year, much like many other Ligonier Valley Historical Society patrons. The season of holiday cheer, Christmas movies, religion, and lavish feasts has evolved over the years into what we know today. To better understand how these practices came to be, we’re exploring some of the commonly shared stories and myths behind Christmas and Santa Claus.

‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

The children were nestled all snug in their beds;

While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads;

And mamma in her’ kerchief, and I in my cap,

Had just settled our brains for a long winter’s nap,[1]

Pagan Christmas

The winter months have long been a time of celebration worldwide. Before Christianity and Jesus, early Europeans celebrated light and birth during the darkest days of the year, winter. People often celebrated during the winter solstice because the worst of winter was behind them, and citizens could expect longer days and extended hours of sunlight.

The Norse celebrated Yule from December 21st, the winter solstice, through January in Scandinavia. In recognition of the return of the sun, fathers and sons would bring home large logs that they would set on fire. Families would feast until the log burned out, which could take as many as 12 days. The Norse believed that each spark from the fire represented a new pig or calf born during the coming year. [2]

The end of the year was often a perfect time to celebrate in most European areas. In December, farmers butchered their cattle, so they didn’t have to feed them during the winter. For this reason, it was the only time of the year when people had a surplus of fresh meat. Lastly, most beer and wine created during the year would finally be done fermenting and ready to consume.

Christian Holiday

As Christianity began to spread, Easter was the main holiday and the birth of Jesus was not a celebrated holiday. In the 4th century, the Christian church decided to institute the birth of Jesus as an official Christian holiday. The Bible does not state the date of Jesus’ birth. Pope Julius I chose December 25th to be the official holiday. Many believe that the church selected this date to absorb and adopt some traditions of the pagans who celebrated the Saturnalia festival. Christmas was first called the Feast of the Nativity and spread to Egypt by 432 and England by the 6th century.

Church leaders believed that by holding Christmas simultaneously with pagan winter solstice festivals, the chance that nonbelievers would embrace Christmas would significantly increase. By the Middle Ages, Christianity had replaced traditional pagan religion. On December 25th, believers attended church, then celebrated the holiday through a carnival-like atmosphere, including alcohol and feasts. This early celebration resembled modern-day Mardi Gras. The lower class would often go to the homes of the rich and demand food and drink. Affluent individuals who failed to host were often terrorized with mischief. Christmas became the time of year when the rich would give back by entertaining the less fortunate citizens. [3]

Christmas Canceled?

England canceled Christmas in the early 17th century. Religious reform brought on by Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan forces took over England in 1645. Cromwell and his followers vowed to rid England of Decadence. As part of his reforms, Christmas celebrations were canceled to focus more on the spiritual side of Christmas. King Charles II was eventually restored to the throne by popular demand. With the return of the king, Christmas returned as well.

Many of the pilgrims and English separatists that came to America were even more conservative in their Puritan beliefs than Cromwell. Due to this fact, Christmas was not a celebrated holiday in early America. From 1659 to 1681, Christmas was outlawed in Boston. During this period, anyone accused of demonstrating holiday spirit would be fined five shillings. However, southern settlements such as Jamestown actively celebrated Christmas. Captain John Smith reported that all enjoyed Christmas and passed without incident.

Many traditional English customs fell out of favor following the American Revolution, including Christmas. Due to its association with the British, the beloved holiday didn’t officially become federal recognized until June 26, 1870.[4]

Saving Christmas

Americans did not begin to embrace Christmas until the 19th century, when they attempted to transform the holiday from a carnival-style celebration towards a more family-focused day of peace and nostalgia.

Americans wanted to shift away from traditional Christmas celebrations because of conflict and turmoil in the 19th century. Unemployment and gang riots from the lower classes often occurred during the Christmas season. A large Christmas riot in 1828 forced New York City’s council to institute the first police force in America. To help prevent violence, upper-class America began to change how Christmas was celebrated.

In 1819, best-selling author Washington Irving wrote The Sketch Book of Geoffrey, a series of stories about the celebration of Christmas in an English manor house. The sketches feature a squire who invited the peasants into his home for the holiday. In contrast to the problems faced in American society, the two groups mingled effortlessly. In Irving’s mind, Christmas should be a peaceful, warm-hearted holiday bringing groups together across lines of wealth or social status. Irving’s fictitious celebrants enjoyed “ancient customs,” including the crowning of a Lord of Misrule. However, Irving’s book was not based on any holiday celebration he had attended. Many historians say that Irving’s account actually “invented” tradition by implying that it described the true customs of the season.[5]

Santa Claus

The origins of Santa Claus start with Saint Nicholas, a 4th century Greek Christian bishop in the Roman Empire, modern-day Turkey. Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of sailors, merchants, archers, repentant thieves, children, brewers, pawnbrokers, unmarried people, and students in various cities and countries around Europe. Saint Nicholas is most well-known for the many miracles he completed and the stories around his generosity.

The story goes that a butcher killed three little children during a famine. The butcher intended to sell the meat to unsuspecting customers. Saint Nicolas, visiting the region, saw through the butcher’s lies and resurrected the children by making the sign of the cross. This incident is one of the many miracles attributed to Nicholas’s memory and legacy.

Nicholas became Father Christmas not because of his miracles but because of his generosity. For women to marry during this period, the bride’s family had to supply a dowry (a payment such as property or money to the groom’s family) to wed. These financial arrangements helped attract suiters and give the new couple financial stability. If you came from a poor family, women would not be able to wed and would have to be sold into slavery or prostitution.

Legend states that a poor man had three daughters. The oldest was beyond the age of marriage. The middle daughter was at the age of marriage, and the youngest daughter was still too young to marry. The eldest daughter told her father to sell her into slavery to prevent her younger sisters from a life of shame and misfortune. Nicolas heard of the situation and decided to help. Nicolas gathered enough money to supply three dowries, one for each daughter. The story goes that Nicolas threw the bags of coins down the home’s chimney, each bag apparently landing in the stockings of each woman while they dried on the mantel. Therefore, we continue to place stockings on the mantel during Christmas because of Saint Nicolas.[6] Saint Nicolas was the original giver of gifts. However, the image of Saint Nicolas has changed due to authors such as Washington Irvine and the commercialization of Christmas.

Christmas Fun Facts

Each year, 30-35 million live Christmas trees are sold in the United States alone. There are about 21,000 Christmas tree growers in the United States, and trees usually grow for roughly 15 years before they are sold.

Christmas was declared a federal holiday in the United States on June 26, 1870.

The first eggnog made in the United States was consumed in Captain John Smith’s 1607 Jamestown Settlement.

Poinsettia plants are named after Joel R. Poinsett, an American minister to Mexico, who brought the red-and-green plant from Mexico to America in 1828.

The Salvation Army has been sending Santa Claus-clad donation collectors into the streets since the 1890s.

Rudolph, “the most famous reindeer of all,” was the product of Robert L. May’s imagination in 1939. The copywriter wrote a poem about the reindeer to help lure customers into the Montgomery Ward department store.

Construction workers started the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree tradition in 1931.

Additional Readings

[1] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43171/a-visit-from-st-nicholas

[2] https://www.history.com/topics/christmas/history-of-christmas

[3] https://www.history.com/topics/christmas/history-of-christmas

[4] https://www.history.com/topics/christmas/history-of-christmas

[5] https://www.history.com/topics/christmas/history-of-christmas

Letter from the Executive Director

Dear Members, Donors, and Lovers of the Compass Inn Museum,

On Behalf of Ligonier Valley Historical Society’s Board of Directors, I am reaching out to you with exciting news for our Compass Inn Museum. However, I must share that this news requires us to cancel our traditional Holiday Candlelight Tours for the 2021 season. We know you will miss them, as we will miss them too. Nevertheless, please read the following message from Netflix to learn why we are so excited.

“We are beyond grateful to the leadership of LVHS for allowing us to use your exquisite Compass Inn as a major filming location for Netflix and Cross Creek’s scripted adaptation of Louis Bayard’s novel, The Pale Blue Eye, starring Christian Bale and being directed by Scott Cooper. The thriller revolves around the attempt to solve a series of murders that took place in 1830 at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Bale will play a veteran detective who investigates the murders, helped by a detail-oriented young cadet played by Henry Melling who will later become the world-famous author, Edgar Allan Poe who bequeathed us the detective genre.

We know that your normal holiday season activities had been curtailed last year due to the Pandemic and understand that shortening them for another season might feel incredibly disappointing. We hope that those disappointments will be offset by the generous donation that has been given to the LVHS and know that you will be able to restore that excitement as the holidays approach in 2022”.

Our final Harvest Tour for the 2021 season is this Saturday, November 20th, from 3-7 pm. Visit Eventbrite to reserve your ticket.

We are still having our annual Festival of Lights in the Community Room of Ligonier’s Town Hall December 4th through 7th from 9 am-5 pm daily. The Toast to the Trees kickoff party will be held on December 3rd, starting at 6:30 pm. Please visit our website at www.compassinn.org for more details and ticket information.

We wish you all a very Happy Thanksgiving and a joyous Holiday season. See you next year as we celebrate the 50th Anniversary of Compass Inn Museum.

Your friend in history,

Theresa Gay Rohall

Executive Director

The History Behind Halloween

The folklore and history behind many of our favorite holidays are often forgotten. To better understand this exciting time of year, Ligonier Valley Historical Society will explore some of the stories and myths behind Halloween.

"In the period leading up to the Great Depression, Halloween had become a time when young men could blow off steam—and cause mischief. Sometimes they went too far. In 1933, parents were outraged when hundreds of teenage boys flipped over cars, sawed-off telephone poles and engaged in other acts of vandalism across the country. People began to refer to that year's holiday as 'Black Halloween,' similarly to the way they referred to the stock market crash four years earlier as 'Black Tuesday.' Rather than banning the holiday, as some demanded, many communities began organizing Halloween activities—and haunted houses—to keep restless would-be pranksters occupied."[1]

Pagan Origins of Halloween

Historians believe that the earliest "Halloween" type festival took place in Ireland and the other Celtic-speaking countries. The Celtic festival of Samhain was celebrated from October 31st to November 1st. Samhain marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter or the “dark half” of the year. People believed that this transition period happened when the boundary between this world and the other worlds thinned. Because of this thinning, it is commonly believed that spirits and fairies could more easily come to this world and actively participate. The Celtic spirits and fairies were both feared and respected. Offerings of food, drink, and crops were often left out as a sacrifice to these spirits so that they might survive the winter. Celtics also believed that the souls of the dead revisited their homes seeking hospitality. The belief that the souls of the dead returned home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and can be seen in many cultures worldwide. In 19th century Ireland, candles would be lit, and prayer would be formally offered for the souls of the dead. After this, the eating, drinking, and games would begin.

Samhain offering to the spirits. Photo from History.com. [10]

Christian Influence

Halloween is the evening before the Christian holy days of All Hallows' Day (November 1st) and All Soul's Day (November 2nd). This gives October 31st the full name of All Hallows' Eve. Major feasts in Christianity have always occurred the night before the holiday, examples being Christmas Eve. Because of this, All Hallows' Eve was incorporated. These three days are collectively called 'Allhallowtide' and are the time for honoring the saints and praying for recently departed souls who have not yet reached heaven.[2]

In 835 CE, All Hallows' Day was officially switched to November 1st, the same day as Samhain, by Pope Gregory IV. It is believed that the Christian church moved the date to match with the Celtic holiday to promote Christianity more easily in previously pagan areas. Creating matching holidays between the church and outside groups can be seen multiple times in Christianity.[3]

By the end of the 12th century, these three days became holy days of obligation across Europe and included ringing church bells for the souls of those in purgatory. It was also customary for criers dressed in black to parade the streets, ringing mourning bells and calling on all good Christians to remember the poor souls. "Souling," the custom of baking and sharing soul cakes for all Christian souls, began in this period as well. Groups of poor people, often children, would go door to door during Allhallowtide, collecting soul cakes in exchange for praying for the dead, especially the souls of the givers' family and friends.

All Saints Day, a shift from offerings to prayer. Photo from AmericanMagazine [11]

This tradition of “souling” is the origin of modern trick or treat. Poor children would go door to door, asking for baked goods in exchange for prayer. This parallels modern trick or treating in many ways. The expression “Trick or Treat” has a darker meaning as well. Trick refers to a threat, usually idle, to perform mischief on the homeowners or property if no treat is delivered.[4]

The holiday of Halloween then moved from Europe with the expansion of European exploration and colonization. Christianity moved with these early Europeans and helped to influence the holiday as we know it today.

Stingy Jack and the Jack-o-lantern

As the story goes, several centuries ago in Ireland, there lived a drunkard known as "Stingy Jack." Jack was known throughout the land as a deceiver or manipulator. On a fateful night, Satan overheard the tale of Jack's evil deeds and silver tongue. Unconvinced (and envious) of the rumors, the devil went to find out for himself whether Jack lived up to his vile reputation.

Jack was stumbling through the countryside when he came upon an eerie grimace-faced man who turned out to be Satan. Jack quickly realized this would be his end. So, Jack made a last request. He asked Satan to let him drink ale one last time before they departed to hell. Satan saw no reason to oppose and took Jack to the local pub where he supplied alcohol. Once Jack had his fill, he asked Satan to pay the tab on the ale. Jack convinced Satan to metamorphose into a silver coin with which to pay the bartender. Satan did so, impressed with Jack's unyielding tactics and silver tongue. Jack then placed the silver coin (Satan) in his pocket next to a crucifix. The crucifix kept Satan from escaping his form, trapping him. Jack agreed to release him in exchange for ten more years with his soul.

Jack-o’-lanterns protecting Compass Inn Museum from Stingy Jack

Ten years later, Satan found Jack again stumbling through the countryside. Jack accepted his fate and prepared to go to hell. However, Jack asked Satan if he could eat an apple from a nearby tree before they departed. Satan agreed and quickly scaled the limbs to retrieve an apple. Jack then surrounded the tree's base with crucifixes carved into the bark, trapping the devil once again. Jack stated that he would release Satan if he promised never to take his soul to hell. Having no choice, Satan agreed and was set free.

Eventually, the years of drinking caught up to Jack, and he died. Jack's soul prepared to enter heaven through the gates of St. Peter but was stopped by God because of his sinful lifestyle. Jack then went down to the gates of hell and begged for admission into the underworld. Satan fulfilled his obligation to Jack and refused to take his soul. Satan gave Jack an ember to light his way. Jack is doomed to roam the world between the planes of good and evil, with only an ember inside a hollow turnip to light his way.[5]

In Ireland and Scotland, people began to make their versions of Jack's lanterns by carving scary faces into turnips and potatoes and placing them in windows or near doors to frighten away Stingy Jack and other wandering spirits. Immigrants from these countries brought the jack-o'-lantern tradition with them when they came to the United States. They soon found that pumpkins, a fruit native to America, make the perfect jack-o'-lanterns.[6] This tradition has continued as many people still believe that Halloween and the changing of the seasons allow spirits to wander the earth. Understanding why we put out jack-o'-lanterns only adds to the fun of the season and Compass Inn Museum's 6th Annual Pumpkin Carving Contest.

Ghost Stories

A ghost is the soul of a dead person or animal that can appear to the living. In ghostlore, descriptions of ghosts vary widely from an invisible presence to translucent or barely visible wispy shapes or realistic lifelike forms. Ghosts are most commonly associated with the spirit of a human being that has not yet passed over into heaven or hell. The soul is either trapped on earth or stayed for a purpose.[7]

The earliest reports of ghosts date back to Mesopotamian religions in the year 3100 BCE with the creation of written history. Ancient Egyptian culture had a widespread belief in spirits and took many steps, such as the pyramids, to help guide and shepherd souls to the afterlife, away from earth. The most notable reference to ghosts in Christianity is in the First Book of Samuel (Samuel 28: 3-19), in which King Saul has the Witch of Endor summon the spirit or ghost of the prophet Samuel.

Ghosts also appear in classical literature, such as Homer's Odyssey and The Iliad. Roman author and statesman Pliny the Young recorded one of the first notable ghost stories in his letter, which became famous for their vivid accounts of life during the peak of the Roman Empire. More modern literature has also depicted ghosts. Edgar Allen Poe and Stephen King are well known for their work regarding ghosts and scary stories. Human spirits that are trapped on earth have been a tale as old as time itself.[8]

There are many famous Americans that are said to have been seen as ghosts. In the late 19th century, Benjamin Franklin's ghost was seen near the library of the American Philosophical Society. Some reports claim that the Ben Franklin statue in front of the society came to life and started dancing in the streets. Additionally, the White House is notorious for ghost stories. No political figure has made so frequent an appearance as the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, who was assassinated in April 1865. The Administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt reported seeing Lincoln's ghost or feeling his presence repeatedly while they guided the country through a time of great upheaval and war.[9]

A recreation of the The Lady in White

Historic places are often the site of ghost encounters. Locations of horrible military battles often report seeing ghosts. The battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, which took place during the Civil War, is infamous for these such stories. Old prisons and places of great torment are often prime locations for ghosts because it is believed that the souls of these people have unfinished business. Ghost stories also occur locally. Tales of the woman in white are repeatedly told in Laughlintown. This ghost is often seen late at night when people are driving through town. Supernatural investigators have also identified Compass Inn Museum as a location of hauntings. Whether or not you believe in ghost stories is irrelevant. These stories have been around since the beginning of written history and will continue.

If you have the courage to learn more about ghosts at Compass Inn Museum, join us for our Halloween Hauntings Storytelling that will take place October 29 to 31 from 6-9 pm.

Additional Reading:

[1] History.com Editors. “9 Creepy Halloween Tales & Traditions.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, October 30, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/halloween-facts-traditions-legends.

[2] “Halloween.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, October 2, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halloween.

[3] History.com Editors. “Halloween 2021.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, November 18, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/halloween/history-of-halloween.

[4] History.com Editors. “How Trick-or-Treating Became a Halloween Tradition.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, October 3, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/halloween-trick-or-treating-origins.

[5] “Stingy Jack.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, October 3, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stingy_Jack.

[6] History.com Editors. “How Jack O'Lanterns Originated in Irish Myth.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, October 25, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/history-of-the-jack-o-lantern-irish-origins.

[7] “Ghost.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, September 23, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghost.

[8] “Ghost Story.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, September 10, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghost_story.

[9] History.com Editors. “History of Ghost Stories.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, October 29, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/halloween/historical-ghost-stories.

[10] History.com Editors. “Samhain.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, April 6, 2018. https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/samhain.

[11] Klein, Terrance. “All Saints Day Is Not Lesser Saints Day.” America Magazine, November 15, 2017. https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2017/10/31/all-saints-day-not-lesser-saints-day.

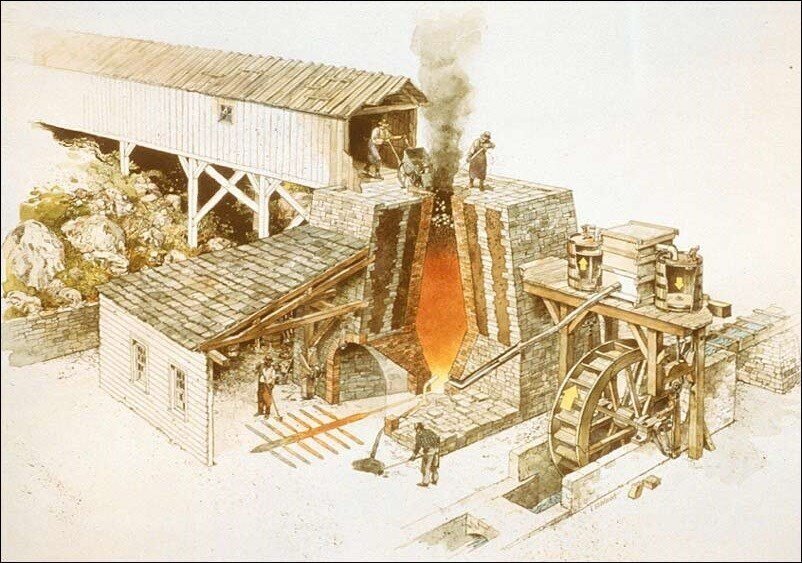

Iron Furnaces in Westmoreland County

Photo by Justin McKeel

The rich history of the Ligioner Valley can be found not only in the towns and communities we call home but also in the forests and the surrounding areas. The bones of an industrial past litter the hills of our valley. These broken structures are becoming harder to find, but the iron furnace lives on in Westmoreland County.

The Iron Industry of Pennsylvania took root in the eighteenth century in the southeastern part of the state, but as the frontier moved westward, ironworks were established not far behind. Furnaces and forgers quickly sprang up to supply the agricultural communities with iron products that were badly needed. The spread of settlements afforded men of initiative and captial the opportunity of producing iron first for a local market and then, in many cases, for more distant markets. [1]

Why Westmoreland County

Iron furnaces have a rich history in Westmoreland County. The abundance of natural resources in the area allowed for cast iron foundries, known as iron furnaces. Iron ore, rocks, and other minerals containing high iron oxides were readily available in the Laurel Highlands. The rich forests of this area also make it the perfect location for early iron furnaces because of the abundance of wood. Wood could be turned into charcoal which is needed for melting iron ore. Westmoreland County originally had sixteen stone-stacked smelting furnaces, also known as iron furnaces. They are named as such:

Westmoreland Furnace – 1792

Hermitage Furnace – 1803

Washington Furnace – 1809

Mount Pleasant Furnace – 1809

Mount Hope Furnace – 1810

Baldwin Furnace – 1810

Hannah Unity Furnace – 1810

Fountain Furnace – 1812

Ross Furnace – 1815

Lockport Furnace – 1844

Laurel Hill Furnace – 1845

Ramsey Furnace – 1847

Conemaugh Furnace – 1847

California Furnace – 1852

Oak Grove Furnace – 1854

Valley Furnace – 1855

(National Park Service, Richard Schlecht, illustrator)

These local furnaces helped supply rural communities with the materials needed to live, farm, and prosper in the new frontier. Additionally, excess iron and pig iron could be sold to major markets in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, helping to bring additional wealth to the region.

The Significance of the Laurel Hill Furnace

The Laurel Hill Furnace was one of 16 iron furnaces constructed in Westmoreland County and one of six located in the northeastern portion of the county. The first iron furnace in Western Pennsylvania was called the Alliance Furnace and was constructed along Jacobs Creek in Fayette County in 1790. In the ensuing half-century, dozens of stone blast furnaces were constructed in Western Pennsylvania, and over time, these furnaces exhibited the changes that marked improvements to the efficiency of the process. By the middle of the 19th Century, the preferred fuel source for firing the iron furnaces had shifted from wood to charcoal to coke, though records suggest that charcoal was still used at Laurel Hill Furnace. Charcoal was produced nearby and likely employed many individuals locally as colliers.[2]

The proportions of the stone furnaces changed, and their overall scale became larger. The shape and capacity of the bellows evolved, and the air produced by the bellows was heated to provide a hot blast into the furnace rather than a cold blast. Some furnaces relied on steam engines for power rather than a waterwheel, though Laurel Hill still relied, at least in part, on the power generated from a waterwheel to provide the blast. The innovation of using fire brick to line the stack is evident at Laurel Hill, but the eventual shift to plate iron or steel shells for the structure of the iron furnace would only become popular beginning around 1860.

The Laurel Hill Iron Furnace, constructed in 1845, is an unusually well-preserved Pennsylvania iron furnace. This 35’ furnace would have significantly boosted the local economy during operation, adding nearly 100 new jobs to the area. The furnace remained in use, producing pig iron, until 1860. The Laurel Hill Furnace is a hot blast charcoal iron furnace situated near Baldwin Run. It stands on land that was initially warranted to Hezekiah Road in 1846. [3]

At its height, the Laurel Hill Furnace employed between 15 and 20 men working around the clock to maintain the operations that created the pig iron produced by the furnace. An additional 40 to 50 workers were needed for supplemental jobs such as cutting wood to make charcoal, hauling the charcoal and pig iron, and transporting the finished products. The Laurel Hill Furnace primarily produced pig iron that was hauled by mules to New Florence for transport on the Conemaugh River and onto the markets in Pittsburgh for manufacture. The furnace also cast household items on-site such as pots, pans, kettles, bells, shoves, and horseshoes for the local population. The furnace complex would have also included a blacksmith shop for finishing these household items and working some of the pig iron and extensive stables for the livestock needed to haul raw and finished products. The weekly output for the furnace averaged 33 tons of pig iron, although it would at times reach 40 tons. [2]

Historical accounts of the furnace estimate that it was out of the blast by 1855 or 1860. An article in The Ligonier Echo indicates that shortly after the furnace went out of blast, a fire destroyed the casting house and other outbuildings, such as the charging bridge and stables. What a quick video by a local amateur historian.

The Production of Charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood or other animal and plant materials in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents.

The production of wood charcoal in locations where wood is abundant dates to ancient times. It generally begins with piling billets of wood on their ends to form a conical pile. Openings are left at the bottom to admit air, with a central shaft serving as a flue. The whole heap is covered with turf or moistened clay. The firing is begun at the bottom of the flue and gradually spreads outward and upward. The success of the operation depends upon the rate of combustion. Under average conditions, wood yields about 60% charcoal by volume or 25% by weight; large-scale methods enabled higher yields of about 90% by the 17th century. The operation is so delicate that it was generally left to colliers — professional charcoal burners. They often lived alone in small huts to tend their woodpiles. Watch a quick video on how this process is done here.

Burying wood to prevent oxygen from reaching the burn [7]

The massive production of charcoal was a major cause of deforestation, especially in Central Europe. The increasing scarcity of easily harvested wood was a significant factor behind the switch to fossil fuel equivalents, mainly coal and brown coal for industrial use. The American form of the charcoal briquette was first invented and patented by Ellsworth B. A. Zwoyer of Pennsylvania in 1897 and was produced by the Zwoyer Fuel Company. The process was further popularized by Henry Ford, who used wood and sawdust byproducts from automobile fabrication as a feedstock. Ford Charcoal went on to become the Kingsford Company.

Iron’s Legacy in Westmoreland County

Iron production decreased and eventually stopped with the creation of modern steel and better casting methods. Manufacturing sites moved to local hubs such as Pittsburgh because it was easier to ship nationally from a hub city. The historic iron industry of Westmoreland County is slowly being lost. Westmoreland Furnace is nothing more than a pile of rubble. The Laurel Hill Furnace, which is under the protection of Ligonier Valley Historical Society, has started to show its age. Trees, weeds, heavy rains, and ice have contributed to this monument’s deterioration. The LVHS is committed to preserving this unique piece of American history. On November 19th, 2020, LVHS and Markosky Engineering Group began mapping the area around the furnace and performing Ground Penetrating Radar studies. LVHS received a Keystone Preservation Planning Grant and a private donation from a local foundation to research the best restoration means. Markosky Engineering spent three weeks doing archaeology work and determining how best to fix the Laurel Hill Furnace. LVHS has also received an additional Keystone Preservation Construction Grant to restore the furnace, but additional funding must still be raised to complete this project.

Photo by Justin McKeel

You can visit this location at 114 Wyoming Ln, New Florence, PA 15944, or donate on our website to help preserve this historic structure.

Additional Information

[1] Harmen, Paul J. “Stone-stack Smelting Furnaces in Westmoreland County.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies Vol 19, No. 2 (1952) 185-193.

[2] Markosky. Cultural Resources Investigation and Recommendations for Stabilization of the Laurel Hill Furnace. Pittsburgh: St. Clair Township, 2020.

[3] Sharp, Myron R. and William H Thomas. A Guide to Old Stone Blast Furnaces in Western Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh: The Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, 1966.

[4] Hopewell Furnace Compound, Protected by the National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/hofu/learn/photosmultimedia/virtualtour.htm

[5] Amateur Historian and Blacksmith Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Me3D0xDqCWM

[6] List and descriptions of existing Iron Furnaces in Pennsylvania. http://www.oldindustry.org/PA_HTML/PaIron.html

[7]“Charcoal Pits.” Hawthorne Valley Farmscape Ecology Program. Accessed September 2, 2021. https://hvfarmscape.org/charcoal

If Ligonier Valley Could Talk: A Brief History of Laughlintown, Pennsylvania

As the Ligonier Valley Historical Society, it’s our duty to share the history of our area. In our new blog series, If Ligonier Valley Could Talk, we’ll explore the histories of faded newspaper clippings and oral histories passed down from generation to generation in Ligonier Valley. Our first post spotlights Laughlintown, home of Compass Inn Museum and Ligonier Valley Historical Society.

But of course, everything happens in towns like Laughlintown. Life and death. Happiness and grief. Hard times, and good ones too. Laughlintown’s story is written in disparate pieces—diary entries; vignettes in old letters now tucked in the back of dresser drawers or stuffed in old boxes in attics; faded newspaper clippings. But, most of all, it is written in memories passed from person to person, family to family, in stories shared through tears and laughter at reunions and funerals and chance meetings of long-lost friends. They are the stories of those who have deep roots here, names which go back to the days when the sound of wagon wheels and the ring of the smith’s hammer echoed along the old “pike.” These names were old when the iron furnaces glow in the night, when six-mule teams haled logs off the mountain, and when the first Mack trucks labored their way noisily over the new Lincoln Highway. – Ralph Kinney Bennett, “God Made This: The Town at the Bottom of the Mountain” [1]

Laughlintown’s Humble Beginnings

Established in 1797, Laughlintown, then known as East Liberty, is the second oldest settlement in Westmoreland County and the oldest in the Ligonier Valley. The name was changed to Laughlintown in the early 1800s in honor of the founder, Robert Laughlin. This change took place because of the creation of the United States Postal Service and the need to have different town names in each community. Laughlintown predates Ligonier which was not incorporated until 1834.

During the French and Indian War in 1758, the British army cut the Forbes Road through Westmoreland County to take Fort Duquesne in Pittsburgh. The Forbes Road continued to be the primary route through the county during the latter half of the eighteenth century. However, by 1785, the state legislature recognized the need for an improved thoroughfare. They authorized the construction of a state wagon road, or the “State Road,” which ran roughly along modern-day Route 30. Also known as the Pennsylvania Road, this route connected Pittsburgh with Philadelphia and accommodated herds of animals and wagons headed west. By the early 1800s, the State Road fell into disrepair. The state legislature responded by settling up the turnpike system, in which private companies improved and maintained sections of the road. Traffic only increased from there.

View of Laughlintown, Pa looking toward the West and Chestnut Ridge- Photo by Seal Burnett 1894

How Geography Influenced Laughlintown’s Development

Geography played a central role in Laughlintown’s development as a resting place for travelers. The town is located at the foot of Laurel Hill, the steepest ridge in the Laurel Mountain Range, making it a natural place for travelers to stop and rest either before or after completing the arduous journey over the mountain. During the turnpike’s heyday, up to 100 Conestoga wagons crossed Laurel Hill, and at least three separate stage lines stopped in Laughlintown daily.

There were also three iron furnaces within a mile of Laughlintown; the Washington, California, and Westmoreland furnaces provided jobs for local residents. In the early nineteenth century, Compass Inn was one of six inns operating in town. In addition to the inns and iron furnaces, Laughlintown also had general stores, blacksmith shops, saddle and harness makers, a wheelwright, a wagon maker, a gingerbread bakery, a tannery, woolen and flour mills, hatter, a tailor and livery stables.

In the early 1800s, Laughlintown saw many notable travelers:

Henry Clay – Senator/Speaker of the House who created the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850

Daniel Webster – a prominent statesman and lawyer who contributed to the passage of the Compromise of 1850, which settled several territorial issues and enacted a new fugitive slave law

Andrew Jackson – an American lawyer, soldier, and statesman who served as the 7th president of the United States and the last president to duel with pistols

William Henry Harrison – an American military officer and politician who served as the 9th president of the United States for 31 days in 1841, becoming the first president to die in office and the shortest-serving U.S. president in history

Zachary Taylor – an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until he died in 1850

Because of its popularity as a rest stop along the turnpike, early nineteenth-century Laughlintown is often compared to today’s Breezewood, the popular hotel and rest stop where Route 70, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, and the Lincoln Highway meet.

Ziders Brothers General Store in Laughlintown, Now The Country Cupboard- Photographer and date unknown

Laughlintown’s Transition from Popular Rest Stop to Quiet Village

Improvements in transportation technology sparked Laughlintown’s decline as a stopover for overland travel. The Western Division of the Pennsylvania Canal was completed in 1831, connecting Johnstown and Pittsburgh, and the Pennsylvania Railroad between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia was finished in the 1850s. While competition from the canal system somewhat affected the stagecoach industry, the railroad devastated it. The railroad bypassed Laughlintown and quickly became the most popular form of travel. As a result, the bustling town of the early 1800s settled down into a quiet village.

In the early nineteenth century, Ligonier and Laughlintown were similar in population and purpose. At the end of the Turnpike Era, however, Ligonier continued to grow because of its location on the Loyalhanna Creek, the active promotion of an organized town, and the establishment of the Ligonier Valley Railroad. Laughlintown, on the other hand, became a small, quiet community. One hundred years after its founding, at the turning of the twentieth century, Laughlintown contained three stores, a gristmill, a blacksmith shop, a wagonmaker shop, a saddlery, and a boarding house.

In 1913, the Lincoln Highway association chose the old Pittsburgh-Philadelphia Turnpike for the new transcontinental highway route through Pennsylvania. This time, it was automobiles instead of stagecoaches and wagons that rolled through the town.

Compass Inn with siding Circa 1910

Laughlintown Today: A Beautiful Historic Destination

Like Ligonier, Laughlintown became a retreat for affluent Pittsburghers who wished to escape the noise and pollution of the city. In the early twentieth century, the wealthy industrialist Richard Beatty Mellon established the Rolling Rock Club on 12,000 acres of land just south of the old turnpike. The club offered space for hunting, fishing, and horseback riding and served as a rural retreat for Mellon’s friends and family. The naming of this establishment took place on a Sunday afternoon in the spring of 1917. Mr. W.L. Mellon, Sr., a nephew of the Mellons, was making a report that day of the progress of work underway, and all through his conversation, he referred to the rushing stream over rocks and the rolling of rocks down the stream bed. His frequent mentioning of this incident impressed Mr. Mellon and prompted him that evening to select the name “Rolling Rock” with the members of his family present. [2] It still operates as an exclusive club today.

Laughlintown today is an unincorporated, primarily residential community of approximately 332 people. Aside from being home to our organization, It’s also home to some light industry and local businesses, including our neighbors at the Original Pie Shoppe. Locals and visitors alike can still see the vital history of this once thriving community in its historic buildings and industrial landmarks, such as the iron furnaces. To learn more about Laughlintown, contact us for more details or visit Compass Inn Museum to experience our rich history firsthand.

Additional Reading

[1] Bennett, Ralph Kinney. “God Made This: The Town at the Bottom of the Mountain.” The

Laughlintown Bicentennial, 1997, 3.

[2] Carlson, A.G. “A Gracious History of Sportsmanship and Stewardship: The Rolling Rock Club.” Laughlintown: Commemorating its 150th Anniversary, 1947, 23.

[3] Sharp, Myron B. “Notes and Quotes on the Compass Inn and the People of Laughlintown, Pennsylvania 1828-1870.” https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/viewFile/3098/2929

[4] “History of Laughlintown.” Ligonier Valley Historical Society. Accessed July 28, 2021. https://www.compassinn.org/history-of-laughlintown

![Samhain offering to the spirits. Photo from History.com. [10]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e07990f5096316889ae357c/1633447883129-CLPZK4PWLP48NP4GA4DO/day-of-the-dead-dia-de-los-muertos-620187692.jpeg)

![All Saints Day, a shift from offerings to prayer. Photo from AmericanMagazine [11]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e07990f5096316889ae357c/1633449601746-R3G3DS80414MXI21KBE2/iStock-153151051.jpg)

![Burying wood to prevent oxygen from reaching the burn [7]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e07990f5096316889ae357c/1630605076003-6K0TC7FMQGT3U7XLN64Z/03b_national_archive_1942_419979_a.jpeg)