Iron Furnaces in Westmoreland County

Photo by Justin McKeel

The rich history of the Ligioner Valley can be found not only in the towns and communities we call home but also in the forests and the surrounding areas. The bones of an industrial past litter the hills of our valley. These broken structures are becoming harder to find, but the iron furnace lives on in Westmoreland County.

The Iron Industry of Pennsylvania took root in the eighteenth century in the southeastern part of the state, but as the frontier moved westward, ironworks were established not far behind. Furnaces and forgers quickly sprang up to supply the agricultural communities with iron products that were badly needed. The spread of settlements afforded men of initiative and captial the opportunity of producing iron first for a local market and then, in many cases, for more distant markets. [1]

Why Westmoreland County

Iron furnaces have a rich history in Westmoreland County. The abundance of natural resources in the area allowed for cast iron foundries, known as iron furnaces. Iron ore, rocks, and other minerals containing high iron oxides were readily available in the Laurel Highlands. The rich forests of this area also make it the perfect location for early iron furnaces because of the abundance of wood. Wood could be turned into charcoal which is needed for melting iron ore. Westmoreland County originally had sixteen stone-stacked smelting furnaces, also known as iron furnaces. They are named as such:

Westmoreland Furnace – 1792

Hermitage Furnace – 1803

Washington Furnace – 1809

Mount Pleasant Furnace – 1809

Mount Hope Furnace – 1810

Baldwin Furnace – 1810

Hannah Unity Furnace – 1810

Fountain Furnace – 1812

Ross Furnace – 1815

Lockport Furnace – 1844

Laurel Hill Furnace – 1845

Ramsey Furnace – 1847

Conemaugh Furnace – 1847

California Furnace – 1852

Oak Grove Furnace – 1854

Valley Furnace – 1855

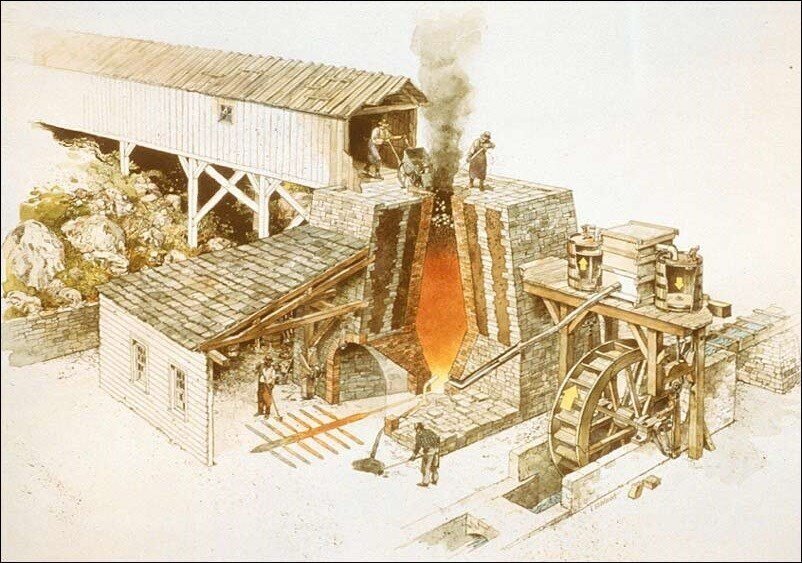

(National Park Service, Richard Schlecht, illustrator)

These local furnaces helped supply rural communities with the materials needed to live, farm, and prosper in the new frontier. Additionally, excess iron and pig iron could be sold to major markets in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, helping to bring additional wealth to the region.

The Significance of the Laurel Hill Furnace

The Laurel Hill Furnace was one of 16 iron furnaces constructed in Westmoreland County and one of six located in the northeastern portion of the county. The first iron furnace in Western Pennsylvania was called the Alliance Furnace and was constructed along Jacobs Creek in Fayette County in 1790. In the ensuing half-century, dozens of stone blast furnaces were constructed in Western Pennsylvania, and over time, these furnaces exhibited the changes that marked improvements to the efficiency of the process. By the middle of the 19th Century, the preferred fuel source for firing the iron furnaces had shifted from wood to charcoal to coke, though records suggest that charcoal was still used at Laurel Hill Furnace. Charcoal was produced nearby and likely employed many individuals locally as colliers.[2]

The proportions of the stone furnaces changed, and their overall scale became larger. The shape and capacity of the bellows evolved, and the air produced by the bellows was heated to provide a hot blast into the furnace rather than a cold blast. Some furnaces relied on steam engines for power rather than a waterwheel, though Laurel Hill still relied, at least in part, on the power generated from a waterwheel to provide the blast. The innovation of using fire brick to line the stack is evident at Laurel Hill, but the eventual shift to plate iron or steel shells for the structure of the iron furnace would only become popular beginning around 1860.

The Laurel Hill Iron Furnace, constructed in 1845, is an unusually well-preserved Pennsylvania iron furnace. This 35’ furnace would have significantly boosted the local economy during operation, adding nearly 100 new jobs to the area. The furnace remained in use, producing pig iron, until 1860. The Laurel Hill Furnace is a hot blast charcoal iron furnace situated near Baldwin Run. It stands on land that was initially warranted to Hezekiah Road in 1846. [3]

At its height, the Laurel Hill Furnace employed between 15 and 20 men working around the clock to maintain the operations that created the pig iron produced by the furnace. An additional 40 to 50 workers were needed for supplemental jobs such as cutting wood to make charcoal, hauling the charcoal and pig iron, and transporting the finished products. The Laurel Hill Furnace primarily produced pig iron that was hauled by mules to New Florence for transport on the Conemaugh River and onto the markets in Pittsburgh for manufacture. The furnace also cast household items on-site such as pots, pans, kettles, bells, shoves, and horseshoes for the local population. The furnace complex would have also included a blacksmith shop for finishing these household items and working some of the pig iron and extensive stables for the livestock needed to haul raw and finished products. The weekly output for the furnace averaged 33 tons of pig iron, although it would at times reach 40 tons. [2]

Historical accounts of the furnace estimate that it was out of the blast by 1855 or 1860. An article in The Ligonier Echo indicates that shortly after the furnace went out of blast, a fire destroyed the casting house and other outbuildings, such as the charging bridge and stables. What a quick video by a local amateur historian.

The Production of Charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood or other animal and plant materials in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents.

The production of wood charcoal in locations where wood is abundant dates to ancient times. It generally begins with piling billets of wood on their ends to form a conical pile. Openings are left at the bottom to admit air, with a central shaft serving as a flue. The whole heap is covered with turf or moistened clay. The firing is begun at the bottom of the flue and gradually spreads outward and upward. The success of the operation depends upon the rate of combustion. Under average conditions, wood yields about 60% charcoal by volume or 25% by weight; large-scale methods enabled higher yields of about 90% by the 17th century. The operation is so delicate that it was generally left to colliers — professional charcoal burners. They often lived alone in small huts to tend their woodpiles. Watch a quick video on how this process is done here.

Burying wood to prevent oxygen from reaching the burn [7]

The massive production of charcoal was a major cause of deforestation, especially in Central Europe. The increasing scarcity of easily harvested wood was a significant factor behind the switch to fossil fuel equivalents, mainly coal and brown coal for industrial use. The American form of the charcoal briquette was first invented and patented by Ellsworth B. A. Zwoyer of Pennsylvania in 1897 and was produced by the Zwoyer Fuel Company. The process was further popularized by Henry Ford, who used wood and sawdust byproducts from automobile fabrication as a feedstock. Ford Charcoal went on to become the Kingsford Company.

Iron’s Legacy in Westmoreland County

Iron production decreased and eventually stopped with the creation of modern steel and better casting methods. Manufacturing sites moved to local hubs such as Pittsburgh because it was easier to ship nationally from a hub city. The historic iron industry of Westmoreland County is slowly being lost. Westmoreland Furnace is nothing more than a pile of rubble. The Laurel Hill Furnace, which is under the protection of Ligonier Valley Historical Society, has started to show its age. Trees, weeds, heavy rains, and ice have contributed to this monument’s deterioration. The LVHS is committed to preserving this unique piece of American history. On November 19th, 2020, LVHS and Markosky Engineering Group began mapping the area around the furnace and performing Ground Penetrating Radar studies. LVHS received a Keystone Preservation Planning Grant and a private donation from a local foundation to research the best restoration means. Markosky Engineering spent three weeks doing archaeology work and determining how best to fix the Laurel Hill Furnace. LVHS has also received an additional Keystone Preservation Construction Grant to restore the furnace, but additional funding must still be raised to complete this project.

Photo by Justin McKeel

You can visit this location at 114 Wyoming Ln, New Florence, PA 15944, or donate on our website to help preserve this historic structure.

Additional Information

[1] Harmen, Paul J. “Stone-stack Smelting Furnaces in Westmoreland County.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies Vol 19, No. 2 (1952) 185-193.

[2] Markosky. Cultural Resources Investigation and Recommendations for Stabilization of the Laurel Hill Furnace. Pittsburgh: St. Clair Township, 2020.

[3] Sharp, Myron R. and William H Thomas. A Guide to Old Stone Blast Furnaces in Western Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh: The Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, 1966.

[4] Hopewell Furnace Compound, Protected by the National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/hofu/learn/photosmultimedia/virtualtour.htm

[5] Amateur Historian and Blacksmith Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Me3D0xDqCWM

[6] List and descriptions of existing Iron Furnaces in Pennsylvania. http://www.oldindustry.org/PA_HTML/PaIron.html

[7]“Charcoal Pits.” Hawthorne Valley Farmscape Ecology Program. Accessed September 2, 2021. https://hvfarmscape.org/charcoal

![Burying wood to prevent oxygen from reaching the burn [7]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e07990f5096316889ae357c/1630605076003-6K0TC7FMQGT3U7XLN64Z/03b_national_archive_1942_419979_a.jpeg)